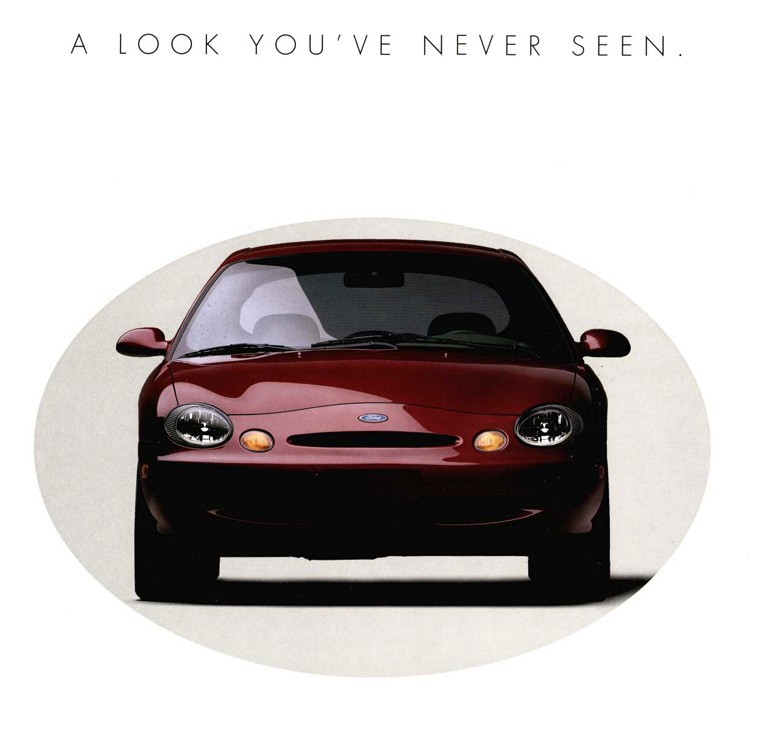

The 1996 Ford Taurus represented a moonshot moment for the automotive giant, much like its revolutionary 1986 predecessor that redefined the American family sedan. Ford’s decision to embark on a third-generation Taurus was rooted in necessity; the once-dominant model was losing its luster, with some whispering that fleet sales were artificially propping up its “best seller” status. The original “jellybean” Taurus charm had faded by the early 90s, demanding a radical redesign, a potential evolution of its iconic shape. Could the team behind “the car that saved Ford” recapture lightning in a bottle, given free rein to innovate once more?

Alt text: Front view of a silver 1996 Ford Taurus SHO parked, showcasing its distinctive oval grille and headlights.

Alt text: Front view of a silver 1996 Ford Taurus SHO parked, showcasing its distinctive oval grille and headlights.

And then, the new Taurus arrived. The reaction was…mixed. While objectively superior to the second-generation model across most metrics, it stumbled on two critical fronts: cost and public perception. The daring new design of the 1996 Taurus alienated potential buyers, and traditional fleet customers balked at the increased price, deeming the upgraded interior features vulnerable to damage by renters and employees. Perhaps the misstep originated in Ford’s choice of muse.

The Ambitious Redesign of the Third-Gen Taurus

Ford sought to recapture the magic of the original Taurus, a car that had shaken up the automotive landscape. The pressure was on to deliver another groundbreaking design. However, the market had shifted, and the design language that resonated in the 80s felt dated by the mid-90s. The challenge was to innovate without losing the core Taurus customer base, a delicate balance that proved elusive. The increasing reliance on fleet sales signaled a weakening public appeal, highlighting the urgent need for a compelling redesign.

Alt text: Side profile of a 1996 Ford Taurus SHO, emphasizing its aerodynamic shape and five-spoke wheels.

Alt text: Side profile of a 1996 Ford Taurus SHO, emphasizing its aerodynamic shape and five-spoke wheels.

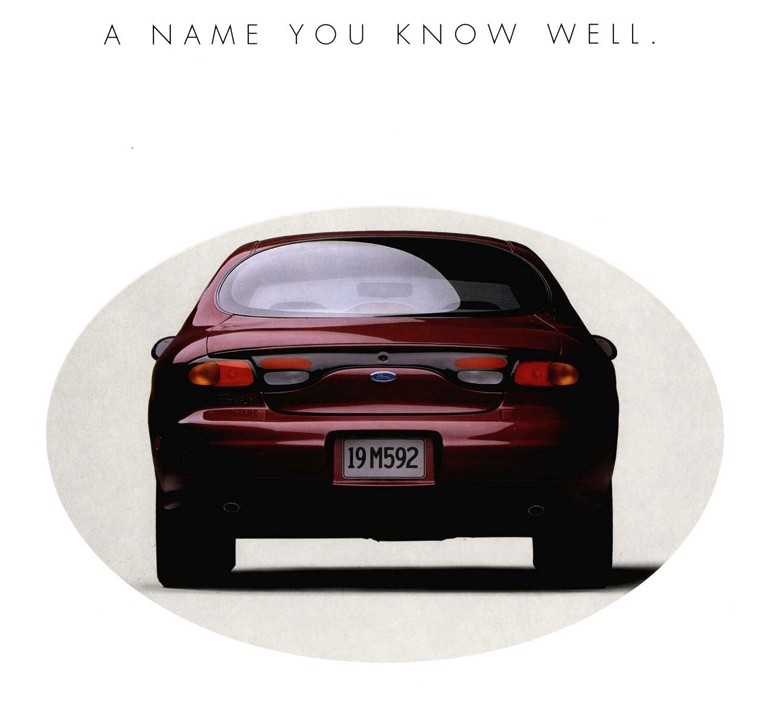

Drawing Inspiration from the Contour Concept

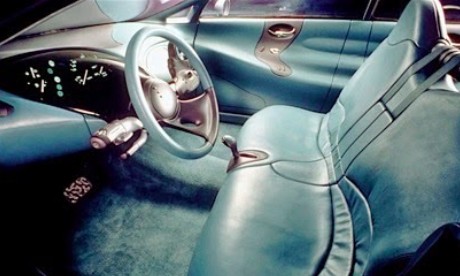

The 1991 Ford Contour Concept offered a glimpse into Ford’s design aspirations – a bold exploration of ovoid shapes and avant-garde aesthetics. While visually striking, the Contour Concept’s radical departure from traditional automotive design proved too extreme for the mainstream Taurus audience. Ironically, these sculptural elements of the Contour Concept conceptually paved the way for the 1996 Ford Taurus, albeit in a form that proved divisive.

Alt text: Rear three-quarter view of the Ford Contour Concept, highlighting its rounded rear design and taillights.

Alt text: Rear three-quarter view of the Ford Contour Concept, highlighting its rounded rear design and taillights.

Alt text: Front view of the Ford Contour Concept, showcasing its oval grille and futuristic headlight design.

Alt text: Front view of the Ford Contour Concept, showcasing its oval grille and futuristic headlight design.

Luxury and Refinement: The Positives

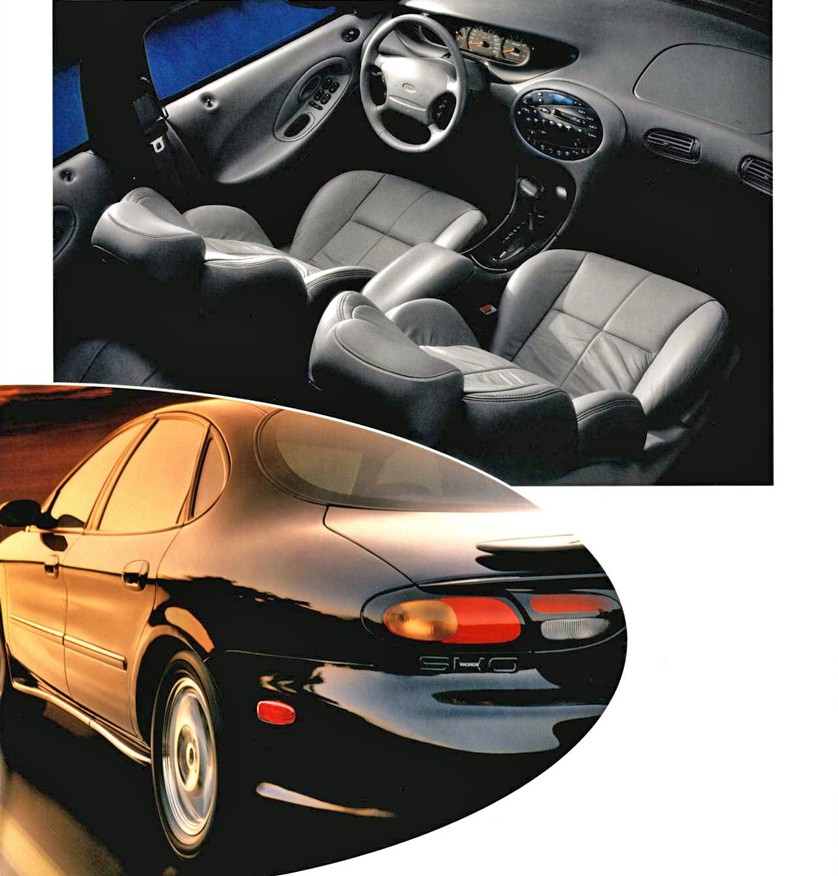

Despite the polarizing styling, the 1996 Taurus marked a significant leap forward in terms of quality and sophistication. Ford prioritized craftsmanship and refinement, resulting in a noticeably more upscale interior. Features like triple-stitched leather seats, generous use of soft-touch plastics, and thoughtful details such as a flip-out console (reminiscent of the Mazda ɛ̃fini MS-8 sedan) elevated the cabin experience. Substantial improvements in NVH (Noise, Vibration, and Harshness) engineering, coupled with a stiffer chassis, contributed to a more refined and comfortable ride. Under the hood, the 3.0-liter, four-cam Duratec V-6 engine delivered a robust 200 horsepower, outperforming competitors like the Camry and Accord.

Alt text: Interior of a 1996 Ford Taurus SHO, focusing on the leather seats, dashboard, and center console.

Alt text: Interior of a 1996 Ford Taurus SHO, focusing on the leather seats, dashboard, and center console.

Ford’s confidence in their revamped family sedan was palpable, even inviting journalists to witness the development process. The Mercury Sable, the Taurus’s sister model, even boasted a backlight grille emblem, a testament to the investment in premium features. However, the pursuit of fleet manager approval and improved profitability led to the elimination of many of these costly features, exemplified by the mid-year introduction of the budget-oriented Taurus G trim.

The Taurus SHO: Performance with a Price

Then came the 1996 Taurus Sho, the high-performance variant. Equipped with a V-8 engine, automatic transmission, and added weight, it ignited considerable debate among enthusiasts. Motorweek‘s review of a Rose Mist Clearcoat Metallic SHO praised its smoothed-out front end, refined V-8 powertrain, ZF variable-orifice power steering, and upgraded seats. Yet, the very qualities that made the 1996 Taurus a comfortable family car somewhat diluted the SHO’s traditionally sporty character and driving dynamics.

The V8 Dilemma: Power vs. Reliability

The most common criticism leveled at the V-8 SHO was its exclusive automatic transmission. While a valid point for purists, the reality was that even V-6 SHOs often opted for automatics, broadening its appeal. Furthermore, the durability of the existing MTX manual transmission with the V-8’s increased torque was questionable.

However, the Achilles’ heel of the third-generation Taurus SHO lay in its Yamaha-engineered V-8 engine. While possessing a pleasing sound, particularly with exhaust modifications, and potentially the best-sounding production V-8, it was plagued by failing cam sprockets. This critical flaw, in an interference engine design, led to the demise of many SHO models, overshadowing the car’s numerous merits.

Alt text: Angled front view of a 1996 Ford Taurus SHO in motion, displaying its front grille and headlights.

Alt text: Angled front view of a 1996 Ford Taurus SHO in motion, displaying its front grille and headlights.

A Missed Opportunity and a Turning Point

In retrospect, the 1996 Taurus, including the SHO variant, can be viewed as a fundamentally good car hampered by design choices and cost-cutting pressures. The styling, while conceptually coherent, proved too radical for the intended audience, inadvertently opening the door for cost reductions. As the Taurus became perceived as cheaper, a negative feedback loop ensued. By the fourth generation in 2000, the distinctive oval rear window vanished, leather seats became less luxurious, and hard plastics returned to the interior in abundance. These changes, in aggregate, made the more refined and reliable Japanese competitors increasingly appealing. The cost-cutting trajectory of the Taurus ultimately contributed to the enduring success of the Accord and Camry.

The third-generation Taurus’s trajectory, in some ways, signaled the dawn of an era dominated by globally designed platforms. These platforms prioritized profitability and manufacturing efficiency over distinctive styling tailored to specific markets, often resulting in more generic and less memorable designs. The era of North American automotive exceptionalism, largely confined to trucks and SUVs by the late 90s, made the Taurus’s design gamble a poignant, if commercially unsuccessful, moment in automotive history. Perhaps the writing was on the wall; the uniquely contoured ovals of the Taurus were destined to be a fleeting phenomenon in the face of broader economic and global automotive forces.