1. Understanding Placenta Previa and Endometriosis: An Overview

Placenta Previa (PP) is a recognized complication in obstetrics, notably increasing the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Approximately half of pregnancies affected by placenta previa experience postpartum hemorrhage [1]. This severe blood loss during or after childbirth contributes significantly to maternal morbidity and mortality, accounting for an estimated 140,000 maternal deaths globally each year [2,3,4,5,6]. Furthermore, placenta previa is a major risk factor for placenta accreta spectrum (PAS), a condition that dramatically escalates surgical risks and mortality. For instance, when placenta previa is combined with PAS, average blood loss during surgery can jump from 1200 mL to 3000 mL, and hysterectomy rates can increase from 3% to 42%. Recent studies have consistently linked endometriosis to a higher incidence of placenta previa [7,8]. While a clear correlation exists between endometriosis and an increased risk of placenta previa [9,10,11,12,13], the impact on surgical outcomes for placenta previa patients who also have endometriosis remains less understood.

Endometriosis is a benign but inflammatory gynecological condition where tissue similar to the uterine lining grows outside the uterus [14]. This misplaced tissue, often including stroma and glands, can lead to muscular metaplasia and reactive fibrosis. In women of reproductive age, endometriosis affects approximately 5–15%, and prevalence rates are rising [15,16,17,18]. Among fertile women, the estimated prevalence of endometriosis is even higher, around 25–50%. The development of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) has improved pregnancy rates for women with endometriosis [15,16,17,18,19]. Consequently, as ART usage increases and more women with endometriosis achieve pregnancy, the number of placenta previa cases in this population may also rise [19,20,21]. In gynecologic surgery, endometriosis has been linked to increased risks of ureteral injury and longer operation times compared to those without this condition [22,23].

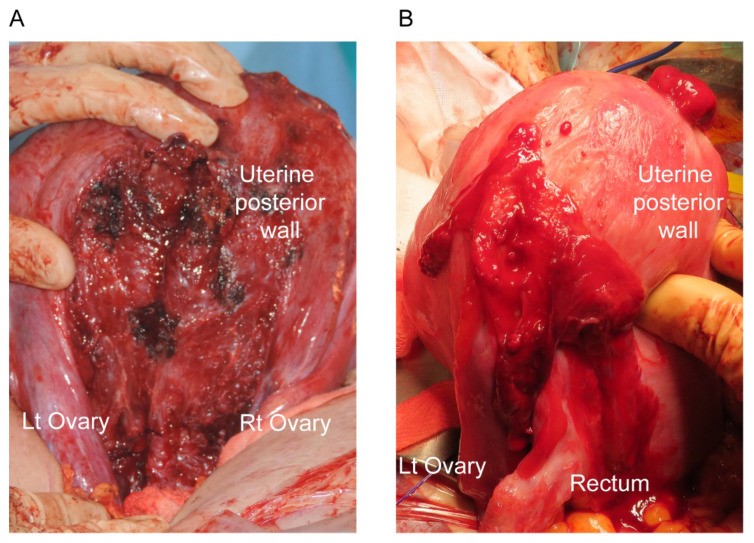

Intraoperative images during cesarean delivery of patients with endometriosis

Intraoperative images during cesarean delivery of patients with endometriosis

For instance, as depicted in Figure 1, women with endometriosis frequently exhibit extrauterine posterior adhesions, which can complicate uterine exteriorization during cesarean deliveries. This suggests that placenta previa patients with endometriosis undergoing cesarean section may face a higher risk of surgical complications compared to placenta previa patients without endometriosis.

This review systematically examines existing literature up to June 2021 to explore clinical research on placenta previa complicated by endometriosis. It also investigates studies that have analyzed the molecular features of placenta previa in the context of endometriosis. Where research directly addressing outcomes in placenta previa patients with endometriosis was lacking, we included relevant narrative reviews focusing on pregnant women with endometriosis to provide a broader context.

2. Defining Endometriosis in Research on Placenta Previa

A previous systematic review by our team assessed the impact of endometriosis on postpartum hemorrhage and placenta previa incidence [24]. That review encompassed 19 studies, each employing its own definition of endometriosis [7,8,11,12,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Among these, 10 studies defined endometriosis during pregnancy as a history of surgery for endometriosis [7,8,11,27,30,31,32,34,36,37]; four others included either prior endometriosis surgery or clinical diagnosis [12,25,33,35]; four studies relied on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 code, and two did not specify their diagnostic criteria. Notably, none of the reviewed studies used intraoperative findings during cesarean delivery, histopathological analysis post-cesarean, or clinical diagnosis of endometriosis during pregnancy as diagnostic criteria. To date, diagnosing endometriosis during pregnancy remains an unaddressed challenge in research.

Considering the limitations in diagnosing endometriosis during pregnancy and building on prior research, this study adopted a comprehensive definition for endometriosis during pregnancy: (i) history of surgery for endometriosis; (ii) clinical diagnosis of endometriosis (based on sonographic findings, pelvic adhesion, uterine posterior adhesion, presence of endometrioma, etc.); (iii) clinical or histopathological diagnosis of endometriosis during cesarean delivery; (iv) classification as endometriosis using an ICD code. Furthermore, we categorized severe endometriosis as revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) stage III-IV endometriosis or deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE).

3. Methodology: Systematic Literature Review on Endometriosis and Previa

3.1. Systematic Review Approach

To comprehensively assess the influence of endometriosis on surgical morbidity in women with placenta previa complicated by endometriosis, we conducted a systematic literature review. We broadened the search terms from our previous review to align with the refined definition of endometriosis used in this study. The primary outcomes of interest were: (i) population-based prevalence of endometriosis during pregnancy; (ii) diagnosis of endometriosis in women with placenta previa during pregnancy; (iii) the impact of endometriosis on placenta previa incidence; (iv) the impact of endometriosis on surgical outcomes for placenta previa patients with endometriosis; and (v) molecular research concerning placenta previa complicated by endometriosis.

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (2020 edition) [40], we performed a systematic search across PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane Library, from their inception to June 30, 2021. We used relevant Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and medical terminology related to placenta previa complicated by endometriosis.

3.2. Data Sources, Inclusion Criteria, and Search Strategy

We screened articles based on titles, abstracts, and full texts, using a modified approach from previous studies [41,42,43,44]. Sa.M. and Sh.M. independently reviewed all abstracts using MeSH terms (see Supplemental Files S1 and S2 for PubMed and Cochrane Library search strategies) to identify studies examining the correlation between endometriosis and placenta previa.

3.3. Study Selection Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) Participants were women with endometriosis as defined in this study; (2) Included women with pelvic adhesion suspected to be due to endometriosis (where over half had clinical or histopathological confirmation); (3) Were original research articles examining outcomes of interest; (4) Reported the incidence of placenta previa complicated by endometriosis; (5) Reported surgical morbidity of placenta previa complicated by endometriosis; (6) Described diagnostic methods for placenta previa complicated by endometriosis; and (7) Were molecular studies focusing on placenta previa complicated by endometriosis.

Studies were excluded if they: (1) lacked sufficient information to determine outcomes of interest; (2) used unclear endometriosis definitions or definitions not aligning with this study; (3) were not published in English; and (4) were case reports, case series, letters, conference abstracts, narrative reviews, systematic reviews, or meta-analyses.

3.4. Data Extraction Process

Sh.M. extracted all relevant data, recording variables such as first author, publication year, study location, number of participants, endometriosis definition, and outcomes of interest. L.M. and Sa.M. independently double-checked the extracted data for accuracy.

3.5. Outcome Measures and Bias Assessment

The primary goal of clinical data analysis was to evaluate the effect of endometriosis on surgical outcomes in placenta previa. Co-primary objectives were to assess endometriosis’s impact on placenta previa incidence and surgical outcomes during cesarean delivery for placenta previa patients. We also examined the effect of severe endometriosis (rASRM stage III-IV, DIE) on placenta previa prevalence. A secondary objective was to review diagnostic approaches for placenta previa complicated by endometriosis. Further outcomes included molecular characteristics of placenta previa complicated by endometriosis.

3.6. Meta-Analysis Strategy

Using eligible data, we calculated the odds ratios (OR) for placenta previa incidence with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using the I2 statistic to quantify total variation proportion. I2 values were interpreted according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0: low (0–30%), moderate (30–60%), substantial (50–90%), and considerable (75–100%) heterogeneity [45].

Meta-analysis and forest plots were generated using RevMan ver. 5.4.1 software (Cochrane Collaboration, Denmark). For pooled analysis, a fixed-effect model was used for studies with low heterogeneity, and a random-effects model for those with moderate to considerable heterogeneity.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Patient demographic differences between groups were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate [46]. All statistical tests were two-sided, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. IBM SPSS Statistics (version 28.0, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all analyses.

4. Results: Endometriosis and Placenta Previa – Key Findings

4.1. Study Characteristics Overview

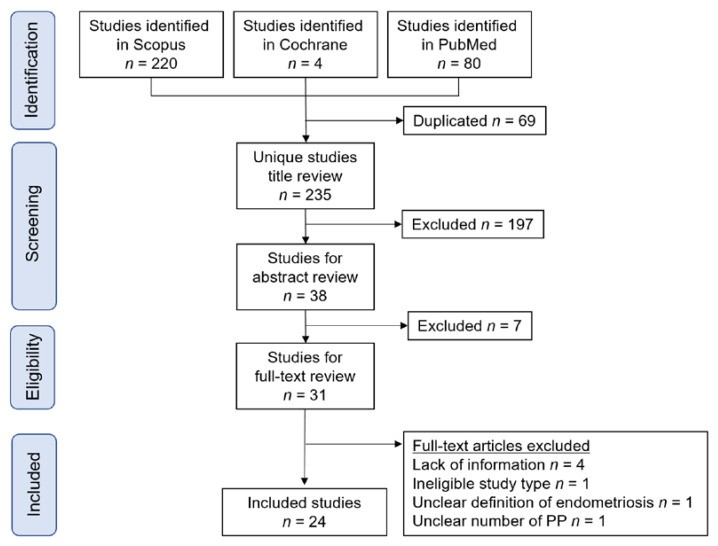

Our systematic literature search aimed to identify studies on the relationship between endometriosis and placenta previa (Figure 2). The search yielded the following number of studies per outcome: (i) population-based prevalence of endometriosis during pregnancy (n = 0); (ii) diagnosis of endometriosis in placenta previa pregnancies (n = 0); (iii) endometriosis influence on placenta previa incidence (n = 23); (iv) endometriosis influence on surgical morbidity in placenta previa patients (n = 1); and (v) molecular studies on placenta previa complicated by endometriosis (n = 0). While a strong correlation between endometriosis and higher placenta previa prevalence exists, our review highlights a significant lack of clinical and molecular research focused specifically on placenta previa complicated by endometriosis.

Study selection scheme of the systematic search of articles

Study selection scheme of the systematic search of articles

4.2. Epidemiology and Clinical Outcomes

4.2.1. Systematic Review Findings on Endometriosis Epidemiology in Pregnancy

Our systematic review found no population-based studies specifically examining endometriosis prevalence during pregnancy. To provide context, we present a narrative review of endometriosis prevalence in the general population.

4.2.2. General Population Prevalence of Endometriosis

Recent population-based studies estimate the overall endometriosis prevalence in the general population between 0.8–2.0% (approximately 3–5% in reproductive-aged women) [20,47,48,49,50,51]. Some studies suggest that endometriosis prevalence is increasing [51]. Given the increased pregnancy rates among women with endometriosis due to ART advancements [15,16,17,18,19], the number of pregnant women with endometriosis is expected to rise [19,20,21]. Therefore, future research is needed to assess the nationwide prevalence of endometriosis specifically during pregnancy.

4.3. The Link Between Placenta Previa and Endometriosis

Systematic Review Results on Previa and Endometriosis Association

We identified 20 comparator studies and three non-comparator studies examining endometriosis’s influence on placenta previa prevalence (Table 1) [7,8,11,12,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,52,53,54,55]. Of these 23 studies, five were population-based and 18 were retrospective. Placenta previa prevalence in pregnant women with endometriosis ranged from 1.7–17.1%, while in those without endometriosis, it ranged from 0.5–4.3%. The non-comparator studies (n=3) focused on patients with severe endometriosis, including DIE or rASRM stage III-IV.

Table 1. Influence of endometriosis on the incidence of placenta previa (PP).

| Author | Year | Area | No. | EndoNo. | SevereCases # | StudyType | IVF | Previa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endo (%) | Control (%) | |||||||

| Comparator studies: women with endometriosis versus women without endometriosis | ||||||||

| Epelboin, S. [25] | 2020 | FRN | 4114833 | 31101 | — | Nationwide | 18.2% | 0 * |

| Yi, W.K. [26] | 2020 | KOR | 1938424 | 44428 | — | Nationwide | — | — |

| Lin, S. [27] | 2020 | CHN | 246 | 82 | — | Retro | — | — |

| Shumueli, A. [28] | 2019 | ISR | 61535 | 135 | — | Retro | 19.3% | 2.6% |

| Miura, M. [12] | 2019 | JPN | 2769 | 80 | — | Retro | 28.7% | 12.8% |

| Uccella, S. [11] | 2019 | ITA | 1808 | 118 | DIE | Retro | — | — |

| Chen, I. [29] | 2018 | CAN | 52202 | 469 | — | Nationwide | — | — |

| Nirgianakis, K. [30] | 2018 | CHE | 248 | 62 | DIE | Retro | 24.2% | 27.4% |

| Berlac, J.F. [7] | 2017 | DEN | 1091251 | 19331 | — | Nationwide | 19.0% | 3.3% |

| Li, H. [31] | 2017 | CHN | 375 | 75 | — | Retro | — | — |

| Mannini, L. [32] | 2017 | ITA | 786 | 262 | DIE | Retro | 26.0% | 10.1% |

| Benaglia, L. [33] | 2016 | ITA | 478 | 239 | — | Retro | All | All |

| Jacques, M. [52] | 2016 | FRN | 226 | 113 | DIE | Retro | All | All |

| Fujii, T. [34] | 2016 | JPN | 604 | 92 | rASRM | Retro | All | All |

| Exacoustos, C. [8] | 2016 | ITA | 341 | 41 | DIE | Retro | — | — |

| Harada, T. [35] | 2016 | JPN | 9186 | 330 | — | Nationwide | 8.8% | 2.2% |

| Baggio, S. [36] | 2015 | ITA | 144 | 51 | DIE | Retro | — | — |

| Lin, H. [37] | 2015 | CHN | 498 | 249 | — | Retro | 0 | 0 |

| Takemura, Y. [38] | 2013 | JPN | 318 | 53 | — | Retro | All | All |

| Healy, D. [39] | 2010 | AUS | 6730 | 1265 | — | Retro | All | All |

| Non-comparator studies: women with endometriosis | ||||||||

| Tuominen, A. [53] | 2021 | FIN | 243 | 243 | DIE | Retro | — | — |

| Farella, M. [54] | 2020 | FRN | 535 | 535 | rASRM | Retro | — | — |

| Vercellini, P. [55] | 2012 | ITA | 419 | 419 | DIE | Retro | 0 | — |

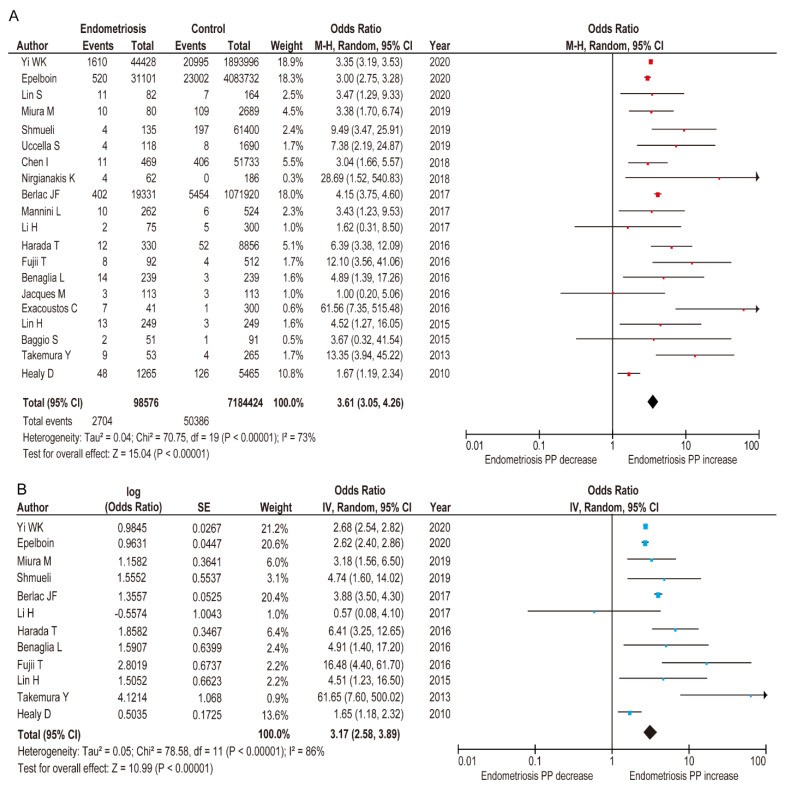

A meta-analysis using the 20 comparator studies from Table 1 [7,8,11,12,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,52] examined endometriosis’s influence on placenta previa prevalence. Due to substantial heterogeneity, a random-effects analysis was applied. Unadjusted pooled analysis (n=20) showed a significant association between endometriosis and increased placenta previa rate compared to women without endometriosis (Figure 3) (OR 3.61, 95%CI 3.05–4.26; heterogeneity: p < 0.001, I2 = 73%).

Meta-analysis of the influence of endometriosis on the occurrence of PP

Meta-analysis of the influence of endometriosis on the occurrence of PP

Although search terms and period were expanded, the adjusted pooled analysis using random-effects models included the same 12 studies as our prior meta-analysis [24]. This analysis confirmed that women with endometriosis had a significantly higher rate of placenta previa (Figure 3) (adjusted OR 3.17, 95% CI 2.58–3.89; heterogeneity: p < 0.001, I2 = 86%) compared to those without endometriosis [7,12,25,26,28,31,33,34,35,37,38,39].

4.4. Severe Endometriosis Significantly Elevates Previa Risk

Systematic Review of Severe Endometriosis and Previa

As shown in Table 2, 11 studies investigated the impact of severe endometriosis on placenta previa incidence in pregnant women. Six compared obstetric outcomes between women with and without DIE; one investigated placenta previa occurrence in women with and without DIE; one evaluated placenta previa incidence in women with DIE; and three assessed the effect of severe endometriosis (rASRM stage III–IV).

Table 2. Effect of severe and non-severe endometriosis on the prevalence of PP.

| Author | Year | No. | EndoNo. | SevereEndo # | SevereNo. | Non-Severe No. | ControlNo. | Previa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe | ||||||||

| Comparator studies: women with DIE versus women without endometriosis | ||||||||

| Uccella, S. [11] | 2019 | 1808 | 118 | DIE | 34 | 84 | 1690 | 4/34 (11.8%) |

| Nirgianakis, K. [30] | 2018 | 248 | 62 | DIE | 62 | — | 186 | 4/62 (6.5%) |

| Mannini, L. [32] | 2017 | 786 | 262 | DIE | 40 | 222 | 518 | 2/40 (5.0%) |

| Jacques, M. [52] † | 2016 | 226 | 113 | DIE | 49 | 64 | 113 | 2/49 (4.1%) |

| Exacoustos, C. [8] | 2016 | 341 | 41 | DIE | 41 | — | 300 | 7/41 (17.1%) |

| Baggio, S. [36] | 2015 | 144 | 51 | DIE | 51 | — | 93 | 2/51 (3.9%) |

| Non-comparator studies: women with DIE | ||||||||

| Tuominen, A. [53] | 2021 | 243 | 243 | DIE | 243 | — | — | 27/243 (11.1%) |

| Vercellini, P. [55] | 2012 | 419 | 419 | DIE | 150 | 269 | — | 9/150 (6.0%) |

| Comparator studies: endometriosis was classified with rASRM | ||||||||

| Farella, M. [54] | 2020 | 535 | 535 | rASRM | 359 | 176 | — | 9/359 (2.5%) |

| Fujii, T. [34] | 2016 | 604 | 92 | rASRM | 43 | 41 | 512 | 7/43 (16.3%) |

| Jacques, M. [52] † | 2016 | 226 | 113 | rASRM | 52 | 59 | 113 | 2/52 (3.8%) |

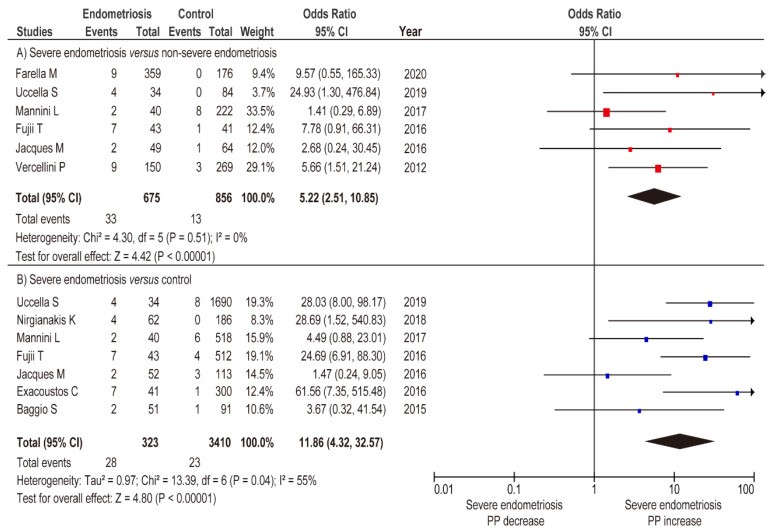

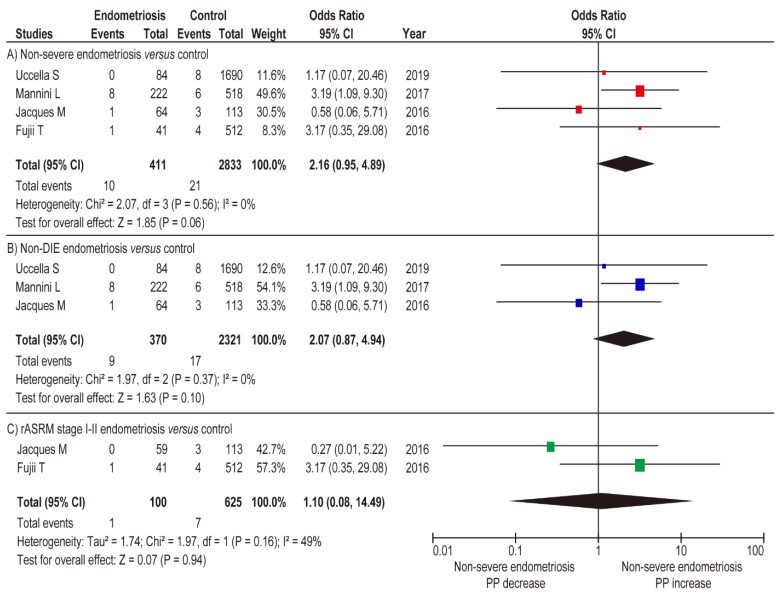

Meta-analysis assessed the impact of severe and non-severe endometriosis on placenta previa rate. Unadjusted random-effects analysis comparing placenta previa incidence in severe versus non-severe endometriosis (Figure 4A) (n=6, OR 5.22, 95% CI 2.51–10.85; heterogeneity: p = 0.051, I2 = 0%) showed significantly higher placenta previa rates in severe endometriosis. Unadjusted fixed-effects analysis showed severe endometriosis was associated with increased placenta previa prevalence (Figure 4B) (OR 11.86, 95% CI 4.32–32.57; heterogeneity: p = 0.04, I2 = 55%), but non-severe endometriosis was not (Figure 5A) (OR 2.16, 95% CI 0.95–4.89; heterogeneity: p = 0.56, I2 = 0%).

Meta-analysis of the influence of severe endometriosis on the incidence of PP

Meta-analysis of the influence of severe endometriosis on the incidence of PP

Influence of non-severe endometriosis on the occurrence of PP

Influence of non-severe endometriosis on the occurrence of PP

Sub-analysis comparing non-DIE endometriosis to women without endometriosis (fixed-effects analysis) showed non-DIE endometriosis was not linked to increased placenta previa rate (Figure 5B) (n=3, OR 2.07, 95% CI 0.87–4.94; heterogeneity: p = 0.37, I2 = 0%). Similar results were found in the comparison of rASRM stage I-II endometriosis versus women without endometriosis (Figure 5C) (n=2, OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.08–14.49; heterogeneity: p = 0.16, I2 = 49%). Meta-analysis results suggest severe endometriosis, but not non-severe endometriosis, is associated with an increased placenta previa rate.

4.5. Surgical Outcomes in Placenta Previa Patients with Endometriosis

Our systematic review identified only one study reporting on surgical morbidity in placenta previa patients with endometriosis [56]. This study included 24 placenta previa patients with posterior extrauterine adhesion. Approximately 20% (5/24) had histologically confirmed endometriosis, 50% (12/24) were diagnosed intraoperatively during cesarean delivery, and 30% (7/24) were suspected of having endometriosis due to infeasible uterine exteriorization from posterior extrauterine adhesion. Propensity score-matching (PS-matching) analysis was used to control for patient background. After PS-matching (n=72), the endometriosis group (n=24) had significantly higher median intraoperative bleeding compared to the control group (n=48) (1.515 mL vs 870 mL, p < 0.01). However, no significant differences were found in operative time, rate of uterine artery embolization, or hysterectomy rates (p = 0.23, p = 0.23, and p = 0.60, respectively).

This retrospective study also found that endometriosis was correlated with a higher rate of total placenta previa (66.7% vs 42.7%, p = 0.04), posterior placenta (95.8% vs 63.2%, p < 0.01), and uterine retroflexion (79.2% vs 36.8%, p < 0.01) [56]. These findings suggest placenta previa complicated by endometriosis is a high risk factor for postpartum hemorrhage, though the cause of increased intraoperative bleeding is still unclear.

4.6. Diagnostic Challenges of Endometriosis in Previa Pregnancies

4.6.1. Systematic Review of Diagnostic Methods

Our systematic review found no studies assessing endometriosis diagnosis specifically in women with placenta previa during pregnancy. Identifying pelvic adhesions through imaging, even in non-pregnant women, remains challenging [57]. This highlights that while a strong association exists between endometriosis and placenta previa, and identifying endometriosis is important, diagnostic methods for endometriosis (excluding endometrioma) during pregnancy are under-researched.

4.6.2. Diagnostic Methods for Extrauterine Posterior Wall Adhesion in Pregnancy

Previously, pregnancy was thought to benefit endometriosis, but systematic reviews evaluating endometriosis progression during pregnancy have refuted this [58]. These reviews concluded that data on endometriosis progression during pregnancy show fewer significant implications than previously believed [58]. As no effective diagnostic method for endometriosis during pregnancy is established, obtaining a medical history of endometriosis or prior endometriosis surgery before pregnancy is crucial.

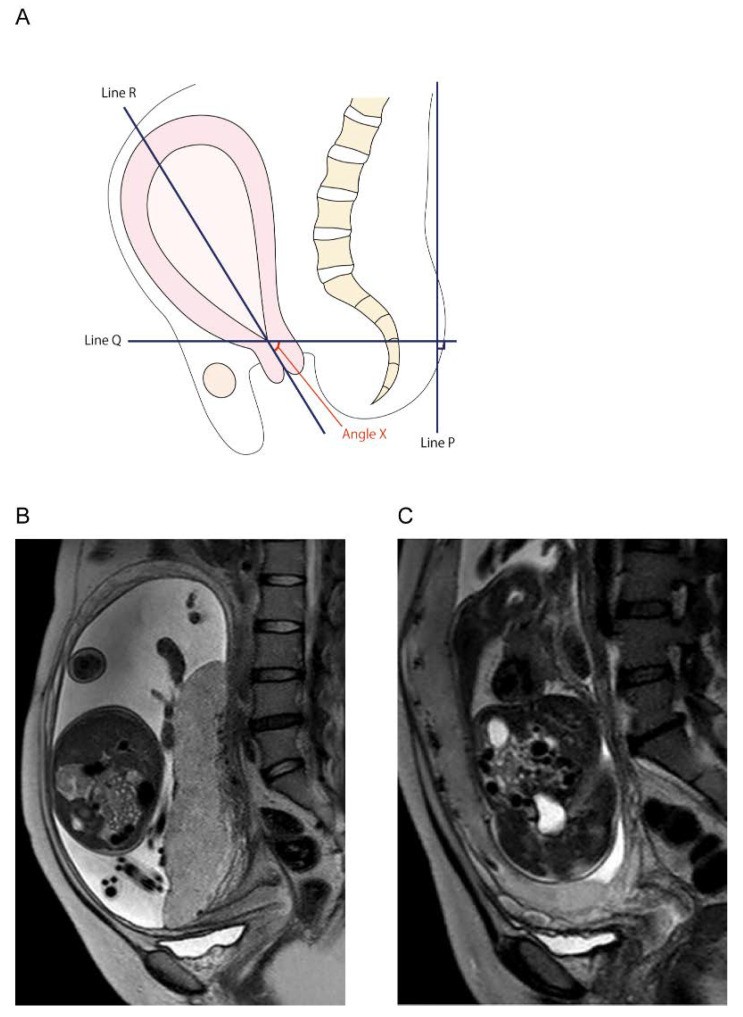

Our prior retrospective study on MRI findings predicting posterior uterine adhesion in placenta previa patients included 96 women with placenta previa, 21 of whom had posterior uterine adhesions. While the cause of posterior extrauterine adhesion was not determined, the study focused on the uterine cervix angle (Figure 6). Women without extrauterine posterior adhesions had a mean cervical canal angle of 38.4°, decreasing by 3.3° weekly. In contrast, the extrauterine posterior adhesion group had a mean angle of 5.95°, increasing by about 0.2° weekly (p < 0.01). This suggests cervical canal angle, measurable by MRI, may predict posterior uterine adhesion in placenta previa patients.

Determination of the cervical canal angle

Determination of the cervical canal angle

5. Molecular Mechanisms Linking Endometriosis and Previa

5.1. Lack of Molecular Research on Previa Complicated by Endometriosis

Our systematic review found no studies investigating the molecular mechanisms of placenta previa complicated by endometriosis. However, some research suggests possible mechanisms for the association between endometriosis and increased placenta previa risk [58].

5.2. Estrogen’s Role in Endometriosis and Potential Previa Link

Prior research proposes that endometriosis development may originate from congenital ectopic or transplanted endometrium, with intracellular estrogen production playing a key role [14]. Aromatase P450, which converts androgens to estrogens [59], is normally expressed in tissues like adipose and ovaries but not typically in the endometrium. However, it has been found in both endometrial and ectopic endometrial tissue in endometriosis patients [14,60]. Furthermore, women with endometriosis often lack the protective 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD) type 2 enzyme [61], which normally lowers levels of potent 17β-estradiol. This combination of local estrogen production and loss of protective mechanisms likely leads to high estradiol levels characteristic of endometriosis and ectopic endometrium [14].

While the link between local estrogen levels and placenta previa rate is undetermined, high serum estradiol during assisted reproductive treatment has been associated with increased placenta previa risk (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.13–1.65) [62]. High serum estradiol can also lead to thicker endometrium, and endometrial thickness >12 mm is linked to increased placenta previa risk (adjusted-OR: 3.74, 95% CI: 1.90–7.34) [63]. Therefore, high serum estrogen and thick endometrium in women with endometriosis may contribute to higher placenta previa rates [63]. Future studies should examine the relationship between serum estrogen levels, local estrogen levels, endometrial thickness, and placenta previa risk.

5.3. Uterine Contractility and Implantation as Potential Mechanisms

Molecular studies exploring mechanisms behind increased placenta previa in endometriosis patients are limited. Successful pregnancy requires: (i) blastocyst implantation; (ii) placentation; and (iii) uterine vasculature remodeling. Delayed implantation can lead to misguidance, potentially resulting in placenta previa, PAS disorders, or placental insufficiency [58,64]. Therefore, delayed implantation is a possible mechanism for increased placenta previa in women with endometriosis.

Inadequate uterine contractility is another potential mechanism. Uterine contractions occur throughout the menstrual cycle and pregnancy [58]. In non-pregnant women, “endometrial waves” involve sub-endometrial myometrium contractions [65]. These contractions, initially low amplitude and frequent in the follicular phase, decrease in frequency and amplitude during the luteal phase to facilitate implantation [66].

Women with endometriosis have been shown to have uterine contractions with higher frequency, amplitude, and basal pressure tone compared to women without endometriosis [67]. Abnormal uterine contractions in women with endometriosis may contribute to the development of placenta previa.

5.4. Inflammation and Pelvic Adhesion in Endometriosis

Endometriosis is recognized as a chronic inflammatory disease, characterized by intraperitoneal inflammation and ectopic endometrial tissue growth [68,69,70]. In the acute phase, ectopic endometrium induces inflammation involving regulatory T (Tregs) and helper T cells [71,72]. Chronic inflammation, sustained by monocytes and macrophages, then promotes angiogenesis and peritoneal adhesion formation [71].

Animal models support these hypotheses. Baboon studies showed decreased Tregs in ectopic endometrium led to increased ectopic endometrial volume and lesion maintenance [73]. Murine models with macrophage depletion showed tissue fragments adhered and implanted, but ectopic endometrial cells failed to organize and develop, unlike controls [70].

Human studies show increased inflammatory mediators in peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis [74,75]. Case-control studies found women with endometriosis had a decreased percentage of CD25 (high) FOXP3+ Treg cells in peripheral blood, but increased percentages in peritoneal fluid [76]. This suggests intraperitoneal Treg cells may suppress effector T cells and promote endometrial stromal cell proliferation and spread [71].

5.5. Genetic Predisposition: Hereditary Genetic Polymorphism

Familial occurrence of endometriosis suggests a genetic basis [77,78,79,80]. Twin studies showed high concordance for endometriosis in monochorionic twins (>80%), indicating genetic factors are involved.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) account for most phenotypic variability [80]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified endometriosis-associated SNPs. Early GWAS (2010-2011) and subsequent studies have highlighted variants like WNT4 rs7521902, IL1A rs6542095, FN1 rs1250248, GREB1 rs13394619, and VEZT rs10859871 as potentially important in endometriosis development [85].

Validating these variants across populations is crucial for understanding endometriosis etiology, improving diagnosis, and enhancing treatment efficacy [80]. Investigating gene expression and polymorphism relationships to endometriosis may lead to new treatments. However, these findings have not yet translated into clinical practice, highlighting the need for future molecular studies to develop personalized endometriosis therapies and potentially reduce placenta previa incidence.

5.6. Somatic Mutations and Endometriosis

The link between endometriosis and ovarian cancer has driven research into somatic mutations in ovarian cancer-related genes [86,87]. KRAS, ARID1A, PIK3CA, and PPP2R1A mutations are frequently observed in endometriosis [88,89].

Exome analysis of DIE nodules showed somatic mutations in ARID1A, KRAS, PIK3CA, and PPP2R1A in 21% of women, confined to glandular epithelial cells [86,90]. Sequencing analysis of endometrioma samples identified hotspot mutations in KRAS and PIK3CA in both endometrium and endometrial epithelium [91]. Increased mutant allele frequency in cancer-related genes in endometriotic epithelium suggests retrograde flow of endometrial cells with cancer-related mutations may lead to endometriosis development [91].

The impact of these mutations on endometriosis development is complex and requires further study. While the endometriosis-ovarian cancer association is well-studied [88,92,93,94,95,96,97,98], their effect on placenta previa prevalence is unknown. Future research should explore this link. Identifying genes mutated in endometriosis may lead to novel treatments to block endometriosis development and reduce placenta previa incidence.

6. Discussion: Implications for Clinical Practice and Future Research on Previa and Endometriosis

6.1. Key Takeaways on Endometriosis and Previa

This study’s key findings are: (i) severe endometriosis is associated with a higher placenta previa prevalence, unlike non-severe endometriosis; (ii) only one study examined surgical morbidity in placenta previa patients with endometriosis; (iii) molecular mechanism research on endometriosis during pregnancy is lacking. While the link between severe endometriosis and increased placenta previa is significant, the reason for the lack of association with non-severe endometriosis requires further investigation.

6.2. Comparison to Existing Research on Previa and Endometriosis

6.2.1. Endometriosis and Placenta Previa Relationship Confirmed

Previous systematic reviews, including our own, have reported that endometriosis correlates with increased placenta previa risk [9,10,58,99]. However, this study uniquely examined the relationship based on endometriosis severity, adding valuable nuance. It’s important to note that our findings are based on univariate pooled analysis with a limited number of studies and may be subject to bias.

6.2.2. Limited Data on Surgical Outcomes for Previa and Endometriosis

Despite the strong association between endometriosis and higher placenta previa risk, data on surgical morbidity in these combined cases remains scarce.

We identified only one study comparing surgical outcomes between placenta previa patients with and without endometriosis [56]. This study suggested that placenta previa complicated by endometriosis increases postpartum hemorrhage risk, but the cause of increased intraoperative bleeding is unclear. While this study is valuable, diagnostic ambiguity in endometriosis assessment and limited patient numbers necessitate cautious interpretation. Future research is needed to confirm these findings.

Hypotheses for increased intraoperative blood loss during cesarean delivery in placenta previa patients with endometriosis were tested, and results indicate: (i) adverse surgical outcomes in women with endometriosis undergoing cesarean delivery [24]; (ii) endometriosis may increase cesarean delivery difficulty due to pelvic adhesions. Reports of high surgical morbidity in cesarean deliveries for women with severe endometriosis, such as DIE, support these hypotheses [8].

6.2.3. Proposed Surgical Treatment for Postpartum Hemorrhage in Previa and Endometriosis Cases

Standard procedures for postpartum hemorrhage in placenta previa cases include uterine compression suture, intrauterine balloon tamponade (IUBT), uterine artery embolization, and hysterectomy [5,103,104,105,106,107,108,109]. Uterine exteriorization is critical for uterine compression sutures, but adhesions from endometriosis can hinder this.

IUBT placement can also be difficult in placenta previa complicated by endometriosis due to uterine retroflexion and a long, narrow cervix [56]. Exteriorizing the uterus to correct retroflexion can worsen bleeding from the uterine posterior wall due to adhesion detachment. Transabdominal or transvaginal IUBT insertion without uterine exteriorization becomes challenging [56].

To improve IUBT placement, we suggest using the Nelaton catheter method for cervical passage. Originally described by Matsubara et al. for quick IUBT placement during cesarean delivery for postpartum hemorrhage in placenta previa cases [110,111,112,113], we modified it to facilitate IUBT insertion without uterine exteriorization through a long, narrow cervix (Figure 7). An intraoperative video of this method is available in Supplemental File S3.

Supplemental File S3 demonstrates Bakri balloon insertion using the modified Matsubara method in a placenta previa case without endometriosis experiencing postpartum hemorrhage. This method allows for quick and easy Bakri balloon placement and successfully controlled postpartum hemorrhage in this case.

6.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Review

This study is likely the first to specifically address surgical outcomes in placenta previa patients with endometriosis. We found that these patients may experience increased intraoperative blood loss during cesarean delivery. Our study also reinforces the correlation between endometriosis and higher placenta previa risk, particularly for severe endometriosis. The meta-analysis comparing severe versus non-severe endometriosis on placenta previa incidence is a novel strength.

However, limitations exist. Retrospective nature of included studies introduces unmeasured bias. Varied endometriosis definitions, limited placenta previa-endometriosis patient numbers, and diagnostic quality in some studies may lead to bias. We only found one study on surgical outcomes in this patient group, and its ambiguous endometriosis definition warrants cautious interpretation and future confirmatory studies.

Women with endometriosis are more likely to conceive via ART [19,114]. While factors like maternal age, ART, and smoking increase placenta previa risk [100,101,102], most included studies [7,8,11,25,26,27,29,30,31,32,35,36,37] lacked multivariate analysis adjusting for obstetric background. This limits our ability to definitively identify endometriosis as an independent placenta previa risk factor due to confounding variables.

Furthermore, studies stratifying placenta previa rate by endometriosis severity (rASRM, DIE) are scarce. The absence of multivariate analysis adjusting for obstetric background also introduces potential bias in our endometriosis-placenta previa association analysis. These limitations should be considered when interpreting meta-analysis results.

6.4. Conclusions and Future Directions

6.4.1. Clinical Practice Implications

Endometriosis is linked to adverse maternal outcomes during cesarean delivery, including postpartum hemorrhage, hysterectomy, and bladder injury. It also increases intraoperative blood loss during cesarean delivery for placenta previa, leading to negative surgical outcomes. Future research should focus on intraoperative treatments to improve surgical outcomes for placenta previa patients with endometriosis.

6.4.2. Clinical Research Directions

Addressing adverse surgical outcomes in placenta previa complicated by endometriosis and improving endometriosis diagnosis are crucial for preventing adverse events. Given MRI’s high cost limiting routine use, future studies should assess transvaginal ultrasonography’s efficacy in diagnosing endometriosis during pregnancy.

6.4.3. Molecular Research Imperatives

While molecular and cellular pathogenesis of endometriosis is increasingly understood, novel treatments to prevent pelvic adhesions and reduce placenta previa incidence in women with endometriosis are lacking. Further research into mechanisms driving increased placenta previa risk in endometriosis is essential for developing these needed therapies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M. Lee, S. Kakuda, H. Sakaguchi, M. Koizumi, M. Watanabe, and T. Hisa for their manuscript preparation assistance.

Supplementary Materials

Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biomedicines9111536/s1, Supplemental File S1: Search strategy for endometriosis diagnosis during pregnancy studies; Supplemental File S2: Search strategy for placenta previa effect on placenta previa rate studies; Supplemental File S3: Intraoperative video of Bakri balloon insertion using modified Matsubara method.

Click here for additional data file.

Author Contributions

S.M. (Shinya Matsuzakiand), Y.N., and Y.U. designed, collaborated, analyzed data, created visuals, interpreted results, and drafted/revised the manuscript. S.M. (Shinya Matsuzakiand) and Y.U. are corresponding authors. S.M. (Satoko Matsuzaki) contributed literature overview, intellectual input, results interpretation, and manuscript editing. M.K., Y.N., and S.K. contributed to study concept/design, analytic approach, and results interpretation. S.M. (Satoko Matsuzaki) and M.M. revised the manuscript. S.K. supervised and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the published version.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Osaka University (No. 16054, approved 14 June 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All included studies are published in the literature.

Conflicts of Interest

Research funding, MSD (S.M.); none for other authors. The funder had no role in study design, conduct, data management, analysis, interpretation, manuscript preparation, or publication decision.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI remains neutral regarding jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

[References]

Associated Data

Supplementary Materials

Click here for additional data file.

Data Availability Statement

All included studies are published in the literature.