French writer Guy de Maupassant harbored a strong dislike for the Eiffel Tower, famously describing it as an “ugly iron skeleton.” Yet, in a curious twist, he frequented the Eiffel Tower daily, often lunching at its base. When questioned about this contradiction, he quipped that it was “the only place in the city where I won’t see it.”

This anecdote perfectly encapsulates the sentiment many feel towards the Tesla Cybertruck. The sheer audacity of its design is so polarizing that perhaps the only way to tolerate its existence is from within its angular confines, shielded from its external presence. If you’re inside, at least you don’t have to look at what you are driving.

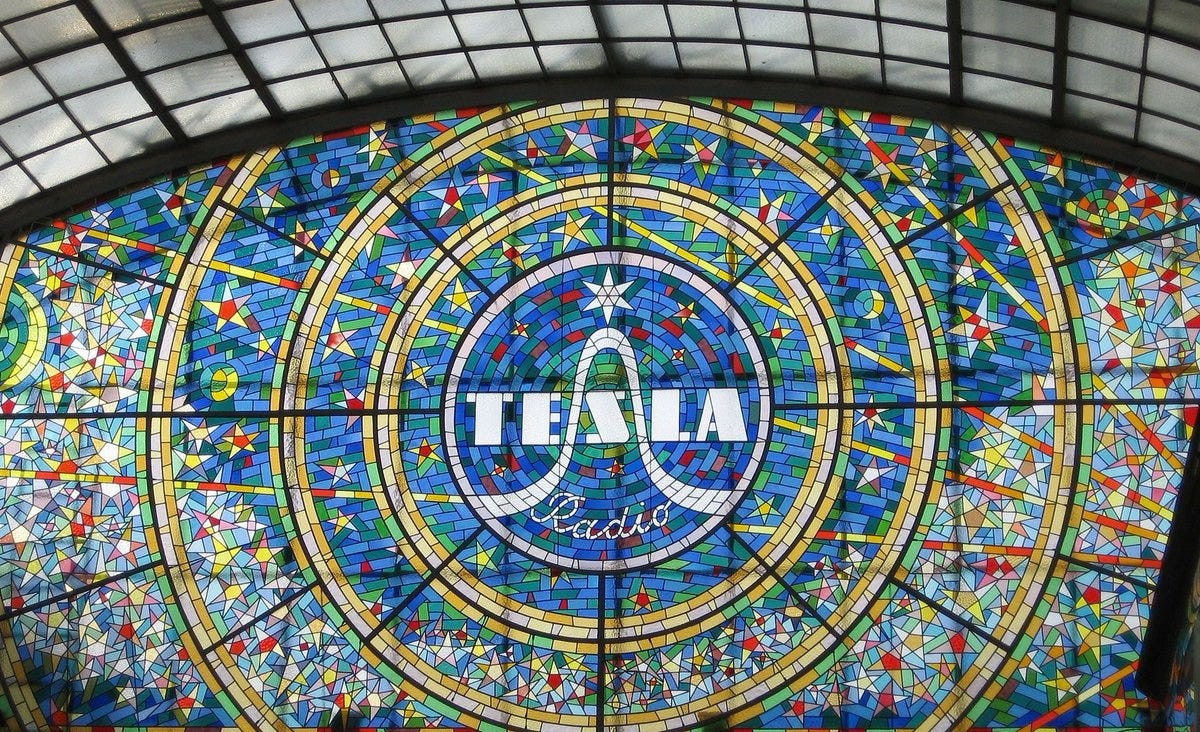

Back in June, a previous article lamented the “banishment of beauty from everyday life,” decrying the decline of aesthetics across various aspects of modern living, from mundane household items to overlooked urban infrastructure. The question was posed: why can’t we have nice things anymore? Examples ranged from vintage Japanese train tickets, showcasing a bygone era of thoughtful design, to the elegant Tesla Radio logo from 1921 – a poignant irony, given the aesthetic chasm between the two entities bearing the Tesla name.

Vintage Japanese train tickets

Vintage Japanese train tickets

Vintage Japanese train tickets showcasing intricate design and attention to detail.

Tesla Radio logo in a stain glass window in Prague, 1921

Tesla Radio logo in a stain glass window in Prague, 1921

The Tesla Radio logo from 1921, a testament to elegant and artistic design, contrasts sharply with modern Tesla vehicle aesthetics.

However, the full weight of contemporary aesthetic degradation didn’t truly sink in until witnessing a Tesla Cybertruck lumbering through suburban streets. Its appearance is less akin to a consumer vehicle and more reminiscent of a militia tank, an ominous harbinger of some impending societal breakdown. This isn’t just automotive design; it’s a statement.

The Cybertruck, much like Maupassant’s Eiffel Tower, invites scorn, yet simultaneously demands attention. It serves as a stark lesson in the current state of aesthetics, revealing uncomfortable truths about our design priorities. For better or worse, this “Tesla Tank Car” – as it appears to many – speaks volumes about the corruption of beauty in our time.

These automotive monstrosities, seemingly birthed from a high school metal shop class gone awry, are becoming increasingly ubiquitous. Their presence diminishes any previous complaints about aesthetic decline, making examples like mundane appliances seem trivial in comparison to this battery-powered behemoth. The Cybertruck isn’t just an ugly car; it’s a cultural artifact, a rolling embodiment of a particular design philosophy.

Contrasting the Cybertruck with the pleasing car designs of the past highlights a fundamental shift in aesthetic values. The word “curvilinear” springs to mind when considering classic automotive beauty. These vehicles appear sculpted, as if inspired by the elegant principles of advanced geometry, seamlessly blending curves and lines into visually intoxicating forms.

Curvilinear car designs of the past

Curvilinear car designs of the past

Examples of classic car designs characterized by curvilinear forms and aesthetic grace.

The Cybertruck, conversely, looks as though it was conceived by a child armed with only a ruler and pen, sketching straight lines onto the back of homework during a fleeting moment of distraction. Its design language is brutally simplistic, devoid of subtlety or nuance.

The stark, angular front design of the Tesla Cybertruck, highlighting its departure from traditional automotive aesthetics.

What exactly is it? A futuristic shipping container? An oversized, angular garbage dumpster? Perhaps a coffin escaped from Dracula’s castle? None of these comparisons are flattering for a vehicle carrying a $100,000 price tag.

A side profile of the Tesla Cybertruck, emphasizing its boxy, stainless steel construction and unconventional silhouette.

Manufactured at Gigafactory Texas, near Austin, the very name of the facility, like the vehicle itself, exudes a jarring blend of grandiosity and absurdity. It evokes the Texan adage, “All hat and no cattle,” perfectly encapsulating the perceived shallowness of the Cybertruck’s design bravado. It’s a vehicle that shouts for attention without possessing genuine aesthetic depth.

However, this critique transcends a mere rant about automotive aesthetics. The Cybertruck serves as a potent symbol of a broader cultural shift. It exposes the darker undercurrents of contemporary aesthetics, mirroring similar trends in architecture and design worldwide. Understanding the Cybertruck’s brutalist appeal is key to understanding much of what’s happening in design today.

The Cybertruck’s Design Philosophy: Power Over Beauty

As the great critic John Ruskin eloquently argued, the human element in art is most evident in the meticulous attention to detail and nuance. This is why he championed Gothic architecture, with its intricate ornamentation and delicate flourishes. Consider also the fluid, organic design of the Sagrada Família in Barcelona, a masterpiece of modern architecture that evokes profound emotional responses.

Antoni Gaudí, its visionary architect, deeply influenced by neo-Gothic principles, famously stated, “The straight line belongs to men, the curved one to God.” Gaudí drew inspiration from the natural world, studying vines, seaweed, oleanders, and other examples of nature’s effortless design elegance. “Nothing is art if it does not come from nature,” he proclaimed.

Intricate details on the facade of the Sagrada Família, showcasing Gaudi’s organic and nature-inspired design philosophy.

This inherent natural quality, so crucial to genuine beauty, is precisely what is absent in the Cybertruck. The vehicle embodies design devoid of subtlety, nuance, or any humanizing elements. It possesses the emotional warmth of a battering ram or a sheet of cold, unyielding metal – both of which it physically resembles.

The core design principle of the Cybertruck is the deliberate replacement of beauty with power. This “tesla tank car” aesthetic is not accidental; it’s intentional. It aims to project intimidation, adopting the visual language of a bully asserting dominance. This aggressive posture is the very essence of its design ethos.

This worldview finds echoes in the Italian Futurists of the early 20th century. Obsessed with speed, machinery, and a rejection of the past, they played a significant role in dehumanizing modern aesthetics. Interestingly, the Futurist movement’s founder, Marinetti, penned his Futurist Manifesto following a car accident – a detail that feels strangely pertinent to the Cybertruck narrative.

Marinetti declared, “Any work of art that lacks a sense of aggression can never be a masterpiece.” This could very well serve as the Cybertruck’s marketing slogan, encapsulating its confrontational design philosophy.

Comparisons to Brutalist architecture are also inevitable. While Brutalism has its proponents who claim to find aesthetic merit in imposing concrete structures, this perspective fundamentally misunderstands Brutalism’s true intent. Like the Cybertruck, Brutalism prioritizes power and imposing presence over conventional beauty. Both design languages communicate dominance and control.

Related reading:

The Most Dangerous Thing in the Culture Right Now Is Beauty

The Banishment of Beauty from Everyday Life

My Alternative Tech Canon—26 Mind-Expanding Books

Recalling the experience of arriving at a new college campus, the comforting familiarity of older buildings, softened by adobe and red tiles, offered solace. These structures, rooted in local traditions and materials, exuded warmth and welcome. In stark contrast, a newer building stood out for its cold, unwelcoming presence.

This building was massive, fortress-like, resembling a bunker designed for post-nuclear fallout survival. Windows were virtually absent, save for the entrance, and the structure was composed of immense, rough-hewn rock. When questioning its stark ugliness, an older student explained its rationale: “They designed this building during a period of student protests and riots. The administration wanted to send a message: We’re more powerful than you.”

You can huff and puff all you want, but you won’t blow this building down! The building’s design became a physical manifestation of institutional power, a chillingly effective deterrent. Ironically, this oppressive structure housed the campus’s “center for educational research,” a deeply unsettling environment for fostering learning and creativity.

Other institutional buildings from that era echoed this sentiment – a visual declaration of hierarchy, of “we’re up, and you’re down.” During the writing of “Work Songs” and “Healing Songs” in San Diego, the Geisel Library served as the primary research location. This famously Brutalist structure, while functional, felt oppressive.

The Geisel Library at UCSD, a prominent example of Brutalist architecture, often cited for its imposing and monolithic design.

Dubbed the Geisel Library, it more closely resembled Darth Vader’s headquarters than a welcoming space for intellectual exploration. Despite its aesthetic shortcomings, it became a daily destination. Each approach to this imposing structure was met with a sense of unease, a visual embodiment of domination and control.

A Google search for “Brutalist architecture” often yields the Geisel Library as a top result. It was within this very building, this monument to aesthetic austerity, that research into the human qualities of artistic creativity was conducted. Perhaps the books themselves were a subconscious rebellion against the oppressive environment in which they were conceived.

The irony deepens with the library’s namesake, Dr. Seuss, whose whimsical and imaginative books were childhood favorites. Yet, the Geisel Library, in its Brutalist severity, proved even less palatable than green eggs and ham.

This encapsulates the essence of the Brutalist aesthetic. Contemporary nostalgia for these structures misses the point entirely. They were never intended to be loved; affection would undermine their purpose. Fear and a sense of disempowerment are the intended outcomes.

And this, arguably, is the underlying purpose of the Tesla Cybertruck design. It’s “fear and loathing time,” emanating from Gigafactory Texas. Only the driver, ensconced within its steel shell, experiences a sense of power. Everyone else becomes mere “cannon fodder” in its wake.

The Cybertruck as a Zombie Apocalypse Vehicle

This aggressive design may explain the reported difficulties in securing insurance for Cybertrucks. The mindset of someone drawn to such an overtly imposing, Napoleonic vehicle might not prioritize cautious driving. The Cybertruck doesn’t just suggest power; it demands right-of-way.

A tweet referencing the challenges and high costs associated with insuring a Tesla Cybertruck.

If this were solely about one aesthetically challenged vehicle and some Brutalist buildings, it might be dismissed as inconsequential aesthetic griping. However, the current cultural embrace of both these visual atrocities is revealing. Raw assertions of power are pervasive in contemporary culture, infecting even art and creativity. This trend was explored in a previous article, “How Did Pop Culture Get So Gloomy?”

The popularity of horror films reflects this cultural gloom. In this context, the Cybertruck emerges as the perfect cinematic accessory. It’s the quintessential vehicle for a zombie apocalypse, ideally suited for mowing down hordes of undead assailants. While compelling in a dystopian movie scenario, its real-world presence in everyday neighborhoods is far less appealing.

There’s a comforting certainty that this aesthetic phase will eventually pass. Even the Cybertruck’s novelty will fade. (Whispers suggest stainless steel’s allure diminishes after a mere six months as rust begins to appear). The current cultural gloom will eventually dissipate, and the pendulum will swing back towards genuine beauty, with its inherent nuances, subtleties, and humanizing qualities.

The beauty revival is on the horizon. There’s no need to wait for Gigafactory Texas to catch up. Sooner or later, even they might yearn to rejoin the world of the aesthetically living.